Week in Review

Week in Review

What We're Reading:

July 27, 2020

COVID-19: Impact by industry. A closer look at the economic fallout of COVID-19 over the next year by sector. Most have been affected by the crisis; only a few will actually benefit. (Grant Thornton)

Mexican economy shrinks further in May to darken recovery prospects. Mexico’s economy shrank another 2.6% in May from April after a record decline the previous month, official data showed on July 20, dimming the chances of a sharp rebound in activity from the economic destruction of the coronavirus pandemic. (Reuters)

With mint at 100%, Argentina imports bills to meet cash thirst. Argentina is rushing to import bank notes as its national mint struggles to keep pace with soaring central bank issuance and inflation of more than 40%. (Bloomberg)

Always rocky, China-US relations appear at a turning point. Four decades after the U.S. established diplomatic ties with Communist China, the relationship between the two may have reached a turning point. (Associated Press)

EU nations clinch $2.1-T budget, coronavirus aid deal after 4 days. Weary European Union leaders finally clinched an unprecedented $2.1 trillion budget and coronavirus recovery fund on July 21, somehow finding unity after four days and as many nights of fighting and wrangling over money and power in one of their longest summits ever. (Business Mirror)

Gulf economies seen shrinking sharply in 2020, to pick up in 2021. Economic activity in the Gulf will contract sharply this year before recovering in 2021, hit by the double shock of the coronavirus pandemic and an oil price crash, a quarterly Reuters poll showed on July 21. (HSN)

Saudi Arabia forces businesses not to trade with Turkey in effort to boost boycott. Saudi Arabia has been putting pressure on local businesses not to trade with Turkey and its industries in a bid to boost its unofficial boycott. The detention of trucks carrying produce from Turkey has raised tension between the two countries. (Middle East Monitor)

Japan starts subsidizing companies to cut reliance on Chinese factories. Japan’s government will start subsidizing some companies to invest in factories in Japan and Southeast Asia as part of efforts to reduce reliance on manufacturing in China. (Business Mirror)

UK trade deal unlikely for now: Britain, EU clash over post-Brexit ties. Britain and the European Union clashed on July 23 over the chances of securing a free trade agreement, with Brussels deeming it “unlikely” but London holding out hope one could be reached in September. (HSN)

Modi’s pandemic gambit. A health calamity is unfolding, yet the government boasts about the best recovery rates in the world. Sound familiar? (Interpreter)

Corporate execs are starting to get skittish about AI. Lately, corporate boards have begun to worry about the ethical ramifications of turning so much power over to the machines. A study of 2,737 executives released this month by consulting firm Deloitte found that a majority of those who used AI in their business reported “major” or “extreme” concerns about ethical risks. (Quartz)

ICC survey shows banks remain optimistic about long-term future of trade finance. Banks are upbeat about the trade finance market in spite of Covid-19-related challenges, according to a report by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). (Global Trade Review)

LatAm sovereign credit still under pressure from coronavirus. The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on Latin America's economic growth and public finances continues to put pressure on sovereign credit profiles, Fitch Ratings says in a new report. This is reflected in the high proportion of sovereign ratings on Negative Outlook in the region, even after a number of downgrades this year. (Fitch)

Fed hoped to skirt a second virus wave. Small businesses may sink in it. The number of outright failures of U.S. small businesses in the first months of the coronavirus pandemic was comparatively modest, but the months ahead look far grimmer as cash balances dwindle, federal help expires, and the disease surges back. (Reuters)

What Does Economic Recovery Look Like Now?

Chris Kuehl, Ph.D.

The world of economic forecasting is a world of assumptions. There is no other method available as far as trying to predict the future. Broad assumptions are easy enough, but timing is tough and that challenge has been on full display as the world contends with the pandemic and the damage inflicted by the economic shutdown.

At the start of this crisis, three important assumptions were made. The first was that the lockdown effort would work as expected and the virus would start to fade dramatically by May. This led to the second assumption: The lockdown would lift as soon as the number of cases fell. That then led to the third assumption and perhaps the most important of the three as far as the health of the economy was concerned: Once the virus was under control and the lockdown was lifted the business community and consumers would return to normal patterns. Currently, it is fairly obvious the first two assumptions have not panned out as expected, but to some degree the third one has even though the other two have not.

The peak in terms of the virus had been reached in April; and in May and June, the numbers had started to fall pretty consistently. In the last few weeks, there have been serious outbreaks in some states and communities, but there are still areas that have maintained better control. The lockdown was lifted in most locations, but not completely. Now the restrictions are being imposed again in response to the outbreaks. In short, the assumptions have been less than accurate.

The economic rebound has nevertheless continued close to the pace that had been anticipated. After two or three months of the worst economic damage seen since the Great Depression, there has been a bounce back in terms of many economic measures. Not that these gains have been enough to repair the damage that had been caused by the lockdown decisions, but they have been trending in the right direction.

There have been gains in the Purchasing Managers’ Index, the Credit Managers’ Index, Industrial production numbers, capacity utilization numbers, durable goods orders, and more. Retail sales have been up by more than 8% for two consecutive months, and there have been gains in sectors such as automotive and housing. Oil prices have climbed out of the cellar as demand has returned. These are all gains relative to the utter collapse that took place the previous two months, but these are gains, nonetheless.

To make any kind of determination as to the future of the U.S. and global economy requires another set of assumptions, and the hope that this time, they prove to be accurate. The first and most important assumption is that consumers will stay engaged because this has been the key factor as far as the current rebound. Once the retailers were allowed to reopen, consumers wasted no time returning to their old consumption habits. This has been the case except for one important area—services.

The lockdown has remained in place for much of the service sector as events have been universally canceled, and there are still many restrictions in place affecting everything from restaurants to personal services. Given that these services account for as much as 65% of consumer spending, this remains a fairly heavy burden on the economic rebound. Thus far the consumer has accepted the idea that it is safe to resume these old patterns, but there has been a steady rise in concern manifesting in the consumer population. That could start to limit the level of participation in the economic recovery.

The other two assumptions are similar to the original set. There is an assumption that the current surge in viral activity will begin to decline to the point that it can be asserted it is coming under control. Given that an effective treatment or a vaccine seems a distant goal, this issue of control becomes paramount. The business sector has begun to state flatly that it will not see real recovery until this criterion is met.

The second assumption is closely related to the prior one. The lockdown must not be reinstituted, and right now it appears that it is indeed making a comeback. Many of the harder hit states and cities are either slowing the process of opening or they are reversing course completely. The potential exists for a return to the crisis months of March, April and May and the acceleration of a full-on recession, which will eliminate any of the gains made thus far.

|

Date & Time Title Speakers Richard “Chip” Thomas, CICP

American Export Training Institute

West Chester, PA

|

Indonesia: Signs of Discontent

The PRS Group

President Joko Widodo’s second term is proving to be even more challenging than his first, despite the government’s solid legislative support, as the COVID-19 pandemic wreaks havoc with the economy, causing mass unemployment and eroding the socioeconomic progress made during Jokowi’s first term. The health crisis has had a direct negative impact on both trade and investment that will only partially be balanced by government initiatives to support businesses, such as a reduction in the corporate income tax, deferred tax payments, and accelerated VAT refunds.

A revival of student militancy, highlighted by protests over legislation that weakened the powers of the Corruption Eradication Commission and proposed revisions to the criminal code designed to appease religious conservatives, holds the potential to become a catalyst for more generalized expressions of popular discontent in a climate of uncertainty and heightened economic insecurity. Critics have castigated Jokowi for appeasing conservative Muslims at the expense of broader public health by turning a blind eye to violations of social distancing rules during Ramadan and relaxing restrictions on internal travel to accommodate the post- Ramadan holiday exodus in late May. The University of Indonesia is now warning that as a result Java could see one million infections by July, resulting in huge pressures on the health-care system.

Due to the delayed response to the pandemic, and the government’s implementation of strategy that fell short of a national lockdown, the economic impact of the crisis is expected to be less severe in Indonesia than elsewhere, with positive real growth forecast for 2020. That said, at less than 1%, the pace of expansion will be well below the norm, and the risk of a contraction will increase if a rising number of COVID-19 cases delays the easing of the restrictions in place.

A strong rebound is possible as the ill effects of COVID-19 eventually dissipate, but it is highly doubtful that growth rates will come close to the government’s target of 7% on any consistent basis as long as corruption and institutional turf wars that impede policy execution and deter investment persist. Administrative and tax reforms will help to attract investment, but the narrow scope of reform efforts will limit the beneficial impact. Real GDP growth will average just 5.2% over the five-year forecast period, in line with the average for 2013–2017, but well below the figure of close to 6% for the 2008–2012 period.

The analysis above is taken from the June 2020 Political Risk Letter (PRL). The best-in-class monthly newsletter, written by the PRS Group, provides concise, easy-to-digest briefs on up to 10 countries, with additional recaps updating prior month’s reports. Each month’s Political and Economic Forecasts Table covers 100 countries, with 18-month and five-year forecasts for KPIs such as turmoil, financial transfer and export market risk. It also includes country rating changes, providing an excellent method of tracking ratings and risk for the countries where credit professionals do business. FCIB and NACM members receive a 10% discount on PRS Country Reports and the PRL by subscribing through FCIB.

Dominant Currencies and the Limits

of Exchange Rate Flexibility

Gustavo Adler, Gita Gopinath and Carolina Osoria Buitron, IMF Research Department

Faced with an unprecedented shock of collapsing global demand and commodity prices, capital outflows, major supply chain disruptions and a generalized drop in global trade, many emerging markets and developing economies’ (EMDEs) currencies have weakened sharply. Will these currency movements support the recovery of these economies?

Building on a new dataset, research laid out in a new IMF Staff Discussion Note indicates that the short-term gains from weaker currencies may be limited. This is especially true for EMDEs where firms price their international sales and finance themselves in a few foreign currencies, notably the U.S. dollar—so-called Dominant Currency Pricing and Dominant Currency Financing.

Dominant currency pricing

The central assumption underlying the traditional view on exchange rates is that firms set their prices in their home currencies. As a result, domestically produced goods and services become cheaper for trading partners when the domestic currency weakens, leading to more demand from them and, thus, more exports. Similarly, when a country’s currency depreciates, imports become more expensive in home currency terms, inducing consumers to import less in favor of domestically produced goods. Thus, if prices are set in the exporter’s currency, a weaker currency can help the domestic economy recover from a negative shock.

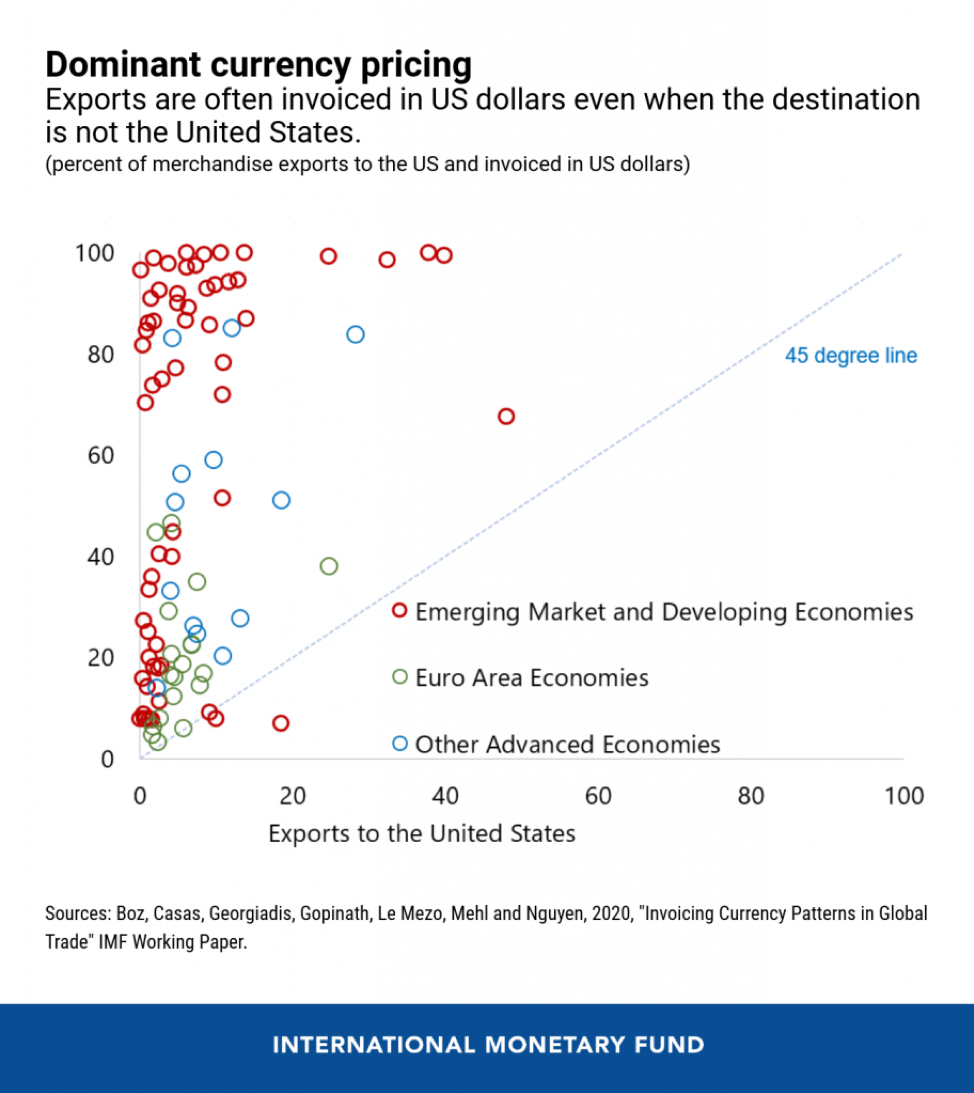

However, there is growing evidence that most of global trade is invoiced in a few currencies, most notably the U.S. dollar—a feature dubbed Dominant Currency Pricing or Dominant Currency Paradigm. In fact, the share of U.S. dollar trade invoicing across countries far exceeds their share of trade with the U.S. This is especially true in EMDEs and, given their growing role in the global economy, increasingly relevant for the international monetary system.

The inception of the euro initially reduced the dominance of the U.S. dollar somewhat, but the latter has remained largely unabated since then. Other reserve currencies play a limited role. Dominant currency pricing is common both in goods and in services trade, although it is less prevalent in the latter—especially in some sectors, like tourism.

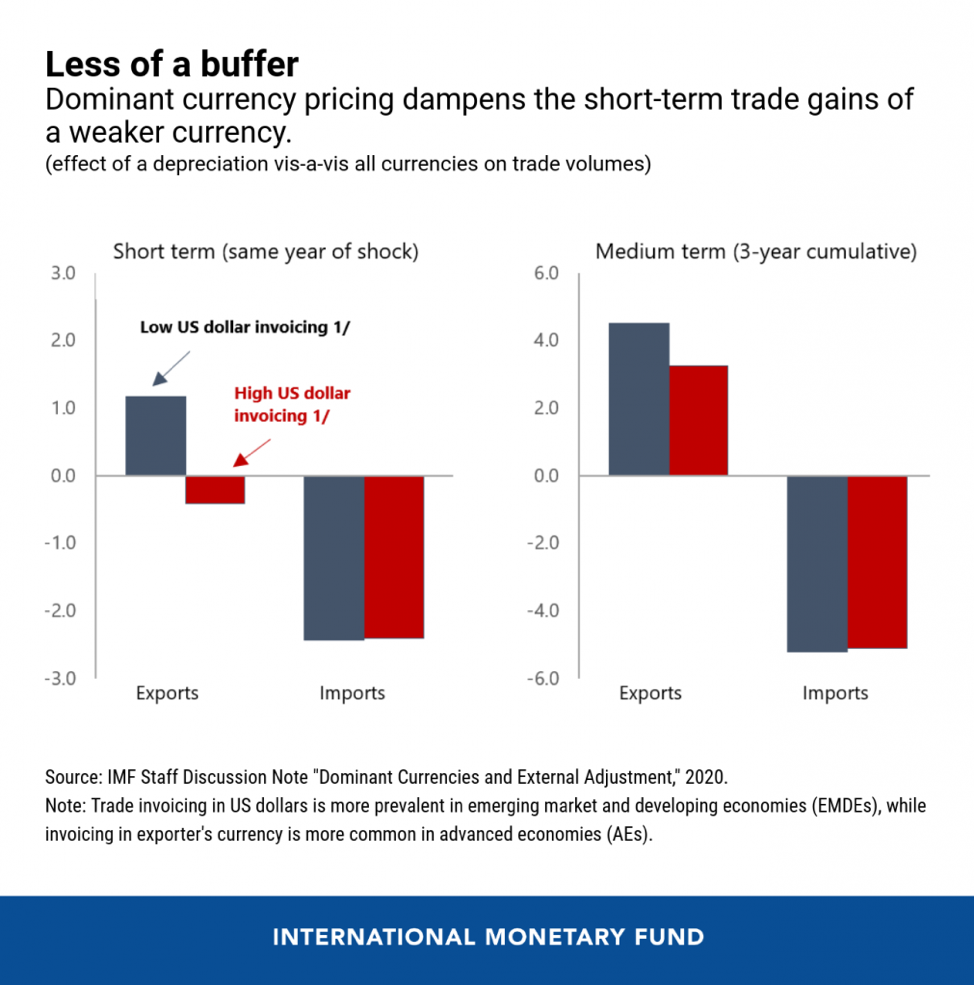

The prevalence of dominant currencies like the U.S. dollar in firms’ pricing decisions alters how trade flows respond to exchange rates, especially in the short term. When export prices are set in U.S. dollars or euros, a country’s depreciation does not make goods and services cheaper for foreign buyers, at least in the short term, creating little incentive to increase demand. Thus, in EMDEs, where dominant currency pricing is more common, the reaction of export quantities to the exchange rate is more muted and so is the short-term boost of a depreciation to the domestic economy.

Another important implication of the use of the U.S. dollar in trade pricing is that a global strengthening of the U.S. dollar entails short-term contractionary effects on trade. This is because the weakening of other countries’ currencies vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar leads to higher domestic currency prices of their imports, including from countries other than the U.S., and, thus, a lower demand for them.

Dominant currency financing

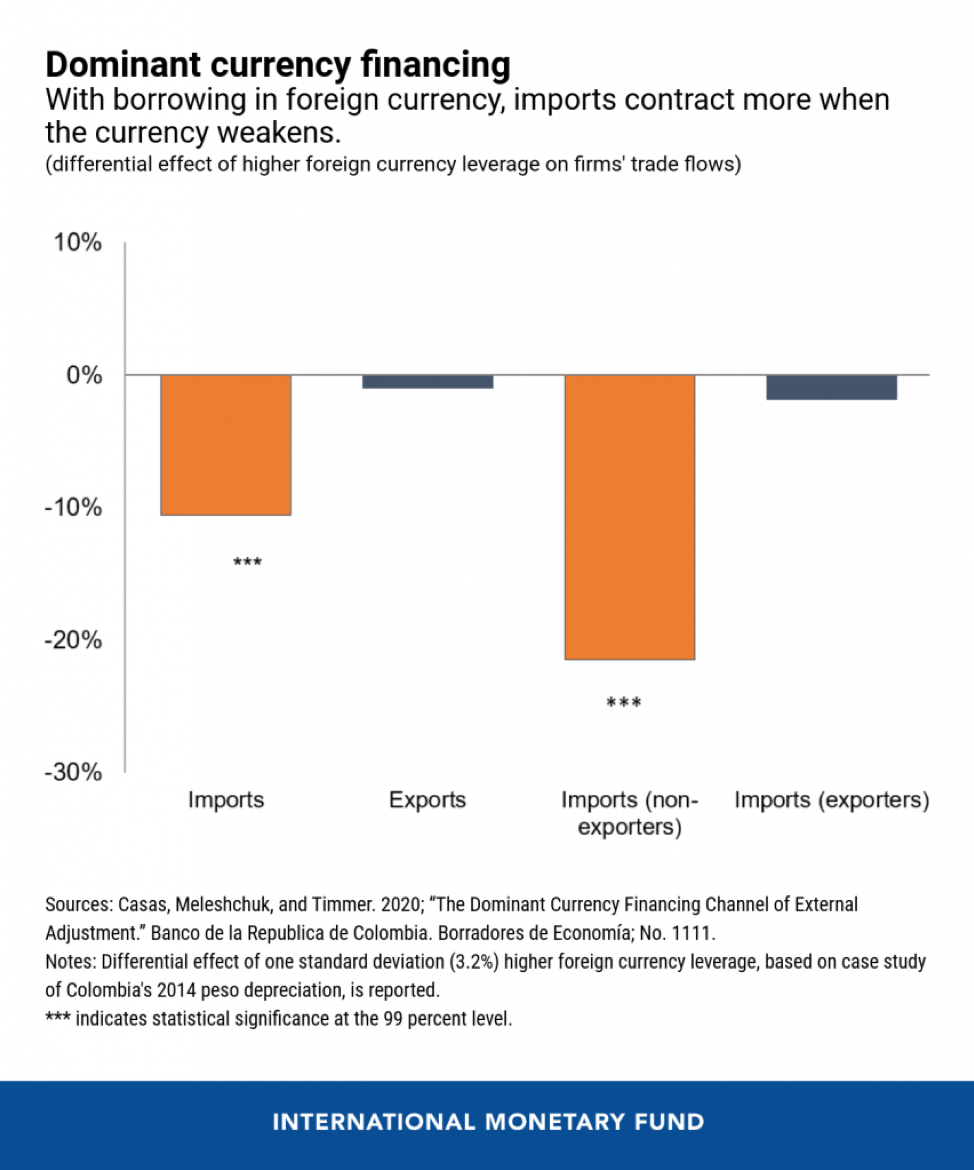

The prevalence of the U.S. dollar is also a feature of corporate financing in EMDEs. This feature—Dominant Currency Financing—means that exchange rate fluctuations can also have effects through their impact on firms’ balance sheets, a phenomenon widely studied in the literature. A depreciation that increases the value of a firm’s liabilities relative to its revenues weakens its balance sheet and hinders access to new financing, as firms’ capacity to repay deteriorates. However, this effect depends on the currency in which revenues are earned, that is, whether revenues are in foreign currency or in local currency.

Exporting firms that use the U.S. dollar or euros for both pricing and financing are “naturally hedged” as liabilities and revenues move in tandem when exchange rates fluctuate. This means foreign currency financing is less of a concern when concentrated in exporting firms. Revenues and liabilities of importing firms, however, are typically not matched, and exchange rate fluctuations bring about balance sheet effects that constrain financing and import volumes. Dominant currency financing tends to amplify the effect of a country’s depreciation on its imports.

The prevalent use of the U.S. dollar in corporate financing also means that a generalized strengthening of the U.S. dollar can have globally contractionary effects through importing firms balance sheets.

Dominant Currencies and the Great Lockdown

Our analysis on dominant currencies suggests that the weakening of EMDE’s currencies is unlikely to provide a material boost to their economies in the short term as the response of most exports will be muted, besides the physical disruptions to trade from supply and demand disruptions. Meanwhile, key sectors that would normally respond more to exchange rates—like tourism—are likely to be impaired by COVID-related containment measures and consumer behavior changes.

Additionally, the global strengthening of the U.S. dollar—which mainly reflects a flight to safe haven assets—is likely to amplify the short-term fall in global trade and economic activity, as both higher domestic prices of traded goods and services and negative balance sheet effects on importing firms, lead to lower import demand among countries other than the United States.

Exchange rates still have a role to play to contain capital outflow pressures and support the recovery over the medium term, but sustaining the domestic economy in the short term requires a decisive use of other policy levers, such as fiscal and monetary stimuli, including through unconventional tools.

Reprinted with permission from IMFBlog.

Week in Review Editorial Team:

Diana Mota, Associate Editor and David Anderson, Member Relations