Week in Review

Global Roundup

November 25, 2019

Week in Review

Global Roundup

November 25, 2019

Mexico urges U.S. Congress not to let politics impede trade deal approval. Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador on Nov. 22 urged U.S. lawmakers not to allow politics to hold up the approval of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) trade deal. (Reuters)

Israeli PM Netanyahu charged with bribery, fraud and breach of trust. Netanyahu becomes the first sitting prime minister in Israel's history to be charged with bribery; a case involving quid pro quo with a telecom tycoon. (Haaretz)

Trump, Kim at odds as deadline looms in nuclear talks. The bonhomie between President Donald J. Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un is nearing a key deadline showing new signs of strain. (Bloomberg)

Afghan elections bring no peace. Continued delays in announcing results have led to calls for an interim government, while the Taliban bide their time. (Interpreter)

European banks face large capital shortfall with Basel III rules. European banks could need as much as 400 billion euros (341.95 billion pounds) in capital to comply with new rules aimed at making the global financial system better able to bear potential losses. (HSN)

The world economy: Synchronized slowdown, precarious outlook. The global economy is in a synchronized slowdown and the IMF is, once again, downgrading growth for 2019 to 3%, its slowest pace since the global financial crisis. (IMF)

Parliamentary elections in Kosovo. On Oct. 7, Kosovo went to the polls. Vetëvendosje was the single-largest party. Meaning ‘self-determination,’ Vetëvendosje has a history of being a protest movement that has criticized the role of the international community in Kosovo.

Political risk an acute issue for LatAm sovereign ratings. Recent political volatility in a number of Latin American countries, including Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador and Peru, reflects a broader theme of rising political risk that could amplify negative sovereign credit trends in the regions. (Fitch)

Trade war threatens tech sectors in China and Silicon Valley. While the U.S.-China trade war rages on, the tensions are exposing growing rifts between China and the Silicon Valley. (Business Mirror)

China central bank cracks down on cryptocurrency trading in Shanghai. China’s central bank launched on Nov. 22 a fresh crackdown on cryptocurrency trading in the financial hub of Shanghai, after Beijing’s promotion of blockchain technology reignited interest in virtual currencies. (Reuters)

The world may have a bigger problem than a potential recession. The global economy is stuck in a rut that it won’t exit unless governments revolutionize policies and how they invest, rather than just hoping for a cyclical upswing, the OECD said. (Bloomberg)

AI poised to impact high-skill U.S. jobs, including finance. Artificial intelligence is coming for America’s high-paid professions as it creates winners and losers across the labor market like never before. (HSN)

Three dead after Colombia protests, as country wakes to transport problems. Three people were killed in events following Nov. 21 marches across Colombia, the defense minister said, as cities woke on Nov. 22 to widespread public transportation problems and calls for another protest. (Reuters)

Working capital management: Where is my cash and why? Technologies such as artificial intelligence have the potential to make it easier for treasurers to gain visibility and control over their cash. But simply investing in these technologies is not enough to achieve working capital efficiencies—treasurers must deploy them in combination with human skills, while reviewing and upgrading existing processes. (TMI)

Middle East Ferment

Chris Kuehl, Ph.D., NACM Economist

It would be possible to write something like this at almost any time in the last 50 years—if not longer. There is no part of the world more fractured and tense than the Middle East. Events today simply add to that long and unhappy record.

The three most immediate concerns involved the status of ISIS, the state of the Iranian economy and the conflict between Saudi Arabia and Iran over the status of Yemen. Lesser but nevertheless important conflicts involved the state of the Lebanese government, the confrontation between the Turkish government and Kurds, the incessant tribal conflicts in Libya, the mutual hostility of factions in Iraq, the lack of a functioning government in Israel and so on. This area of the world has been a political and diplomatic quagmire for generations, but lately there has been a new wrinkle in all this. The biggest change has been the status of oil.

The U.S. and other nations felt compelled to engage in the Middle East chaos because the oil wealth of the region drove the economies of the rest of the world. It is not that this oil is no longer important as Europe and Asia still depend heavily on the oil states in the area. The fact is the U.S. is now the world’s largest oil producer and nations such as Canada, Mexico, Norway, U.K., Brazil, Nigeria, Angola and many others play a far greater role than in past decades. The role of oil has changed and so have the dynamics in this region.

It can be argued that the primary interest of the U.S. in this area is now fighting terrorism rather than protecting oil access. Even this focus on terror has changed. The main goal of the U.S. has been to isolate terror groups as opposed to actually trying to defeat them. The U.S. has not ended ISIS, but it has less global reach than before—at least that is the assumption. The U.S. withdrawal from Syria gave ISIS a boost, but it is not clear that ISIS constitutes a direct threat to the U.S.—it will depend on the tactics it chooses to pursue going forward.

The decline in the price of oil and the sanction pressure on Iran has severely weakened the Iranian economy. That has created a great deal of frustration within the country. It has also weakened its ability to interfere in the region through support of groups such as the Houthi and Hezbollah.

The U.S. has not walked away completely from the region, but the presence is far less than in the past and now seems highly reactive. The U.S. maintains its support for Israel, but nobody is sure who is in charge there at the moment. There is still support for the Saudi kingdom, but a more limited one and the U.S. has been less and less engaged in Iraq. The nations that have been moving into that void are Russia and Turkey. Nobody is quite sure what their goals are at this point.

-

APRIL

24

11am ET -

Where the Buck Stops: Establishing KYC &

Export Compliance Best Practices

Speaker: Paul J. DiVecchio, principal of DiVecchio & Associates

Duration: 60 minutes

-

Just a Little off the Top: Strategies for Reducing the Growing Cost of B2B Credit Card Acceptance

Speakers: Lowenstein Sandler Partner Andrew Behlmann and

Colleen Restel, Esq.

Duration: 60 minute -

APRIL

29

3pm ET

-

MAY

7

11am ET -

Collections 101

Speaker: JoAnn Malz, CCE, ICCE, Director of Credit, Collections, and

Billing with The Imagine Group

Duration: 60 minutes

-

Author Chat: How to Lead When You’re Not in Charge

Author: Clay Scroggins

Duration: 90 minutes | Complimentary -

MAY

8

11am ET

Trade War Driving Growth in Global Trade into Negative Territory

Atradius N.V.

A 0.6% contraction in global trade growth is expected this year with only a modest recovery to 1.5% growth in 2020, predicts Atradius N.V. The U.S.-China trade war is the biggest contributor to the slowing growth, however issues in other large, emerging market economies, spill-overs from Germany’s automotive and manufacturing slump and Brexit-motivated stagnation of European economies are also contributing to the slowdown, the trade credit insurer noted.

The rift between the U.S. and China is directly affecting almost 4% of global trade, roughly USD 700 billion. However, more important are the indirect effects that are being felt throughout the world. The uncertainty it creates, in particular, weighs heavily on business investment. That in turn negatively affects value chains and trade flows.

Despite all the uncertainty and disruption, consumers continue to spend and unemployment remains in check. With inflation stubbornly low, loosening monetary policy and tight labor markets supporting increased participation and rising wages, the consumer outlook remains positive for the near term. However, with the consumer being the lone pillar supporting economic growth, any shock to consumer confidence could destabilize the economy and reverse growth expectations in 2020.

“The trade war is having a profound effect on global trade,” said John Lorié, chief economist of Atradius N.V. “If it expands to other economies in Asia and Europe, which is very possible, we could see an even more pronounced slowing in trade. The uncertainty created by this and other economic and political developments around the globe are really challenging economic growth. While we don’t foresee a global recession at this stage, the outlook is very weak with a high risk of further slowing.”

For Venezuela’s Neighbors,

Mass Migration Brings Economic Costs and Benefits

Emilio Fernandez Corugedo, Senior Economist,

and Jaime Guajardo, Deputy Division Chief, of IMF’s Western Hemisphere Department

The world’s newest migration crisis is unfolding in Latin America, where Venezuela’s economic collapse and unprecedented humanitarian crisis has sparked a wave of emigration to neighboring countries. While these countries are providing helpful support to migrants in many areas, large migration flows have strained public services and labor markets in these countries.

According to the Response for Venezuelans, which is a joint International Organization for Migration and UNHCR platform, the total number of migrants leaving Venezuela reached about 4.6 million in November 2019—with about 3.8 million settled in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Without a clear end in sight to the crisis and amid rising social tensions across the region, how can Latin American governments best craft a coordinated response that serves the needs of refugees while protecting their citizens and economies? Striking this balance will be critical, but also potentially beneficial.

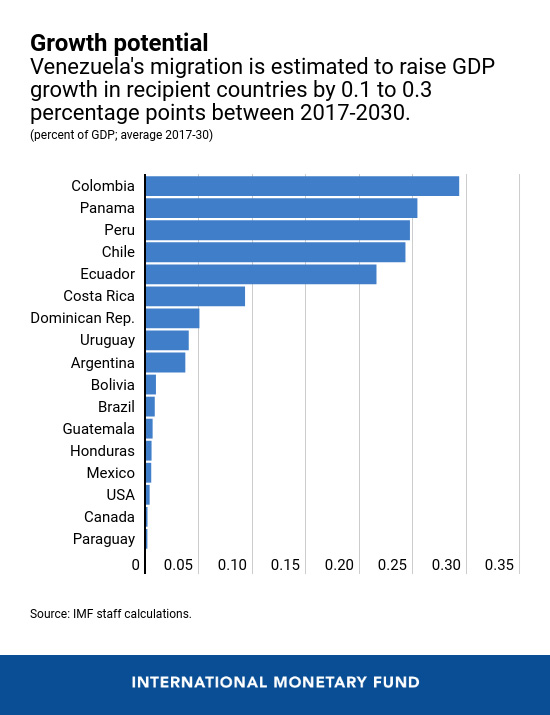

Our latest research finds that Venezuela’s migration can potentially raise GDP growth in receiving countries by 0.1 to 0.3 percentage points during 2017–2030. Policies, including greater support for education and integration into the workforce, could help migrants find better-paying jobs and, ultimately, help raise growth prospects for countries receiving migrants.

Crisis and Exodus

Since the beginning of the crisis, living conditions have severely deteriorated for Venezuela’s 31 million inhabitants. Extreme poverty rose from 10% of the population in 2014 to 85% in 2018. And severe shortages of food and medicines continue to plague the population.

Making matters worse is the sharp drop in economic activity, which has contracted by around 65% between 2013 and 2019. This was driven by plummeting oil production, worsening conditions in other sectors and pervasive electricity blackouts.

Meanwhile, hyperinflation continues unabated with monthly price increases of about 100%, rivaling other historic hyperinflation episodes.

Facing these harsh living and economic conditions, migrants are fleeing Venezuela and settling in neighboring countries.

Colombia has received the largest share, followed by Peru, Ecuador, Chile and Brazil. Migration flows to some countries in the Caribbean and Central America have been even larger relative to their local populations, though smaller in absolute numbers.

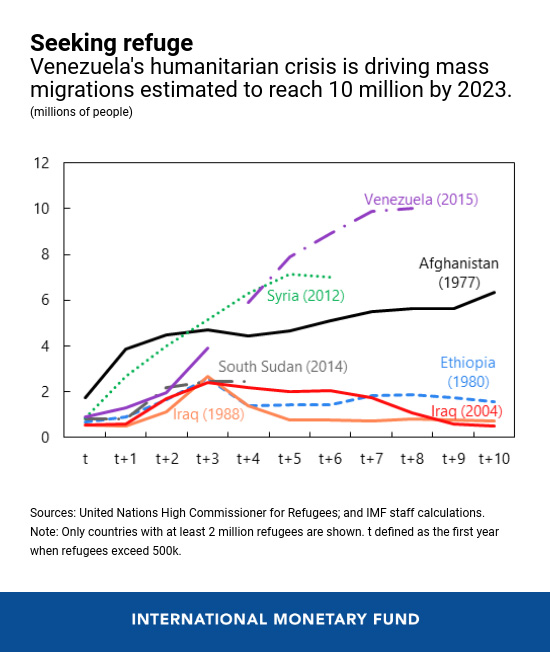

Based on current trends, our research projects that the total number of migrants could reach 10 million in 2023—although with a wide range of uncertainty around this figure. If realized, Venezuela’s mass migration would overtake past refugee crises—for instance, Syria in the 2010s or Afghanistan in the 1980s.

Regional spillovers

What does an exodus of this scale imply for the region? Spillovers from large migration flows from Venezuela are expected to place immediate pressures on fiscal spending and labor markets in recipient economies, but over time they would also contribute to higher economic growth.

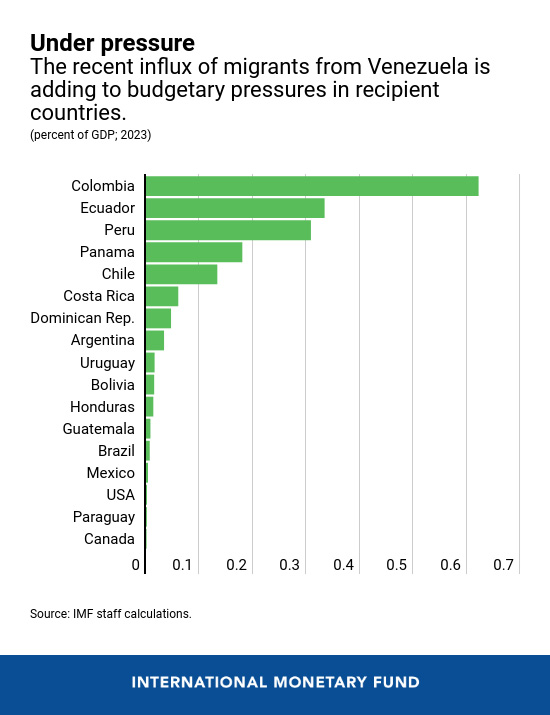

On budgetary pressures, receiving nations are providing helpful support to migrants in the form of humanitarian aid, basic healthcare, education, validation of educational titles and job search.

Using detailed data for Colombia on each of these categories as a benchmark, estimates suggest that public spending related to growing migrant populations could reach around 0.6% of GDP in Colombia by 2023, 0.3% in Ecuador and Peru, and 0.1% in Chile.

The overall impact on the fiscal deficit would be smaller than what the higher spending would imply, because tax revenue would also increase as the economy expands.

Over time, real GDP growth is expected to increase as the size and skills of the labor force expand, as many Venezuelan migrants bring relatively high levels of education and skills. Factors such as language and culture may also help migrants from Venezuela integrate more easily into regional economies in Latin America compared to other recent migration episodes. The expansion of the labor force would also lead to higher investment.

In the near term, however, the influx of migrants—depending on the speed and scale of the inflows—can place pressure on labor markets to absorb them, displace some local workers and increase informality.

Taking into account the age, size and skill levels of migrants, as well as the fact that most have taken low-skilled jobs in the informal sector, Venezuela’s migration is estimated to raise GDP growth in recipient countries by 0.1 to 0.3 percentage points during 2017–2030.

The growth impact could be larger and more immediate if migrants can find jobs in line with their educational level—a transition that can be made easier by policies.

Policy Challenges

A key challenge for policymakers in the region is how to manage the transition at a time when their economies have slowed, and many countries need to reduce their fiscal deficits.

In the near term, facilitating the integration of migrants into the domestic labor market and easing the process to validate their professional titles or to set up businesses would maximize the impact on growth and minimize the need for public support.

Multilaterally, international cooperation to assist the main receptors of Venezuelan migrants with the costs of migrant assistance should be considered. Individual country actions toward migrants, such as border restrictions, can complicate the situation for other partners—pointing to the need for a more regional approach.

Looking further ahead, providing migrants with access to education and healthcare will be key to ensuring they live long and productively to benefit not only themselves but also the economies in which they reside.

Reprinted with permission from the IMF.

Week in Review Editorial Team:

Diana Mota, Associate Editor and David Anderson, Member Relations