Week in Review

Global Roundup

October 21, 2019

European goods hit by new US tariffs. The U.S. imposed tariffs on $7.5bn on EU goods just after midnight in Washington DC on Oct. 17, after the World Trade Organization ruled in its favor earlier this month. (BBC News)

Despite trade truce, US-China cold war edges closer. Mutual mistrust, U.S. concerns about national security, human rights widen split between two countries. (Wall Street Journal)

Trudeau could lose power in Canada’s election Monday. Polls show Trudeau could lose to his Conservative Party rival in national elections on Oct. 21 or fail to win a majority of seats in Parliament and have to rely on an opposition party to remain in power. (Associated Press)

Brexit on a knife edge as PM Johnson stakes all on 'Super Saturday' vote. Britain’s exit from the European Union hung on a knife-edge on Oct. 18 as Prime Minister Boris Johnson scrambled to persuade doubters to rally behind his last-minute European Union divorce deal in an extraordinary vote in parliament. (Reuters)

Brexit insolvency fears boost demand for trade credit insurance. Companies are stepping up purchases of insurance to protect themselves against insolvencies in Britain, industry sources say, in part due to concerns about the impact of Brexit. (HSN)

Turkey-Syria offensive: Disastrous moment for US Mid-East policy. It has taken a week to reshape the map of the Syrian war, in the seven days since President Donald Trump used what he called his "great and unmatched wisdom" to order the withdrawal of U.S. troops from northern Syria. (BBC News)

Austria blocks “nice on paper” EU-Mercosur trade deal. Austria has rejected the free trade pact between the EU and South America’s Mercosur trade bloc, a heavy blow to the 20-year-in-the-making deal. (Global Trade Review)

China’s GDP growth grinds to near 30-year low as tariffs hit production. China’s third-quarter economic growth slowed more than expected and to its weakest pace in almost three decades as the bruising U.S. trade war hit factory production, boosting the case for Beijing to roll out fresh support. (HSN)

‘Strong Countermeasures’: After U.S. House Passes Bills Backing Hong Kong Protests, China Threatens Retaliation. The U.S. House of Representatives passed three measures on Oct. 15 in support of the protests in Hong Kong, and Beijing responded on Oct. 16 saying it will retaliate if the bills pass into law. (Fortune)

The beginning of the end of a US role in the Middle East? President Trump’s abrupt withdrawal of all U.S. troops in northeastern Syria brings to mind Great Britain’s 1968 retreat “East of Suez.” It marked an inflection point, a final abandoning of empire given London’s limited financial resources, lapsed political will and heightened anti-colonial hostility. Is the U.S. approaching its own “East of Suez” moment? (The Hill)

Peace is slipping away in Colombia. The 2016 agreement between FARC and the Colombian government is in jeopardy. What’s worse, Washington has turned a blind eye to the Colombian president’s slipshod implementation of the accord. The Trump administration’s negligence may abet the spread of drug violence or reignite the conflict. (Foreign Affairs)

Is There a Brexit Deal or Not?

Chris Kuehl, Ph.D., NACM Economist

The British Parliament put Prime Minister Boris Johnson in a box several weeks ago by passing legislation that would require him to push the Brexit deadline into some time next year if a deal with the EU was not struck by Oct. 31.

Delay was most definitely not in Johnson’s best political interest and would likely have accelerated calls for a new election. Given he has been disappointing his Brexiter supporters, he would not have fared well according to polls.

The last-minute deal with the EU means he has technically met the requirement, but the deal is anything but certain. In most respects, it resembles the deal Theresa May tried to pass through Parliament because the EU has not budged on any of the key issues.

Johnson now has to get the support of the Conservatives to make the deal a reality, and that doesn’t seem any easier than it was for May.

As soon as the deal was announced, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) announced that it was not willing to support it. That instantly robbed Johnson of 10 supporters in Parliament. Johnson was counting on members of the DUP to want to avoid a chaotic hard exit, but they are extremely angry at the prospect of customs duties between Northern Ireland and Ireland.

Johnson seems to hope other Brexiters will choose to back the deal in order to avoid the “no-deal” departure, but the real issue is what the EU will do if this deal is not approved by the British.

There have been some very hardline statements from some in the EU. They assert they will accept the no-deal option rather than extend these fruitless negotiations for months and months more. At the same time, there have been comments from Donald Tusk that contradict this tough position and open the possibility of more talks.

The Brexiter faction may choose to force the EU to make that choice. The odds are an extension will be proposed and approved but not without some assurance by the U.K. that positions will change. By the same token, the U.K. will demand EU positions remain flexible as well. Thus far, there has been no sign of flexibility on the part of either side, but that intransigence has led absolutely nowhere.

-

APRIL

24

11am ET -

Where the Buck Stops: Establishing KYC &

Export Compliance Best Practices

Speaker: Paul J. DiVecchio, principal of DiVecchio & Associates

Duration: 60 minutes

-

Just a Little off the Top: Strategies for Reducing the Growing Cost of B2B Credit Card Acceptance

Speakers: Lowenstein Sandler Partner Andrew Behlmann and

Colleen Restel, Esq.

Duration: 60 minute -

APRIL

29

3pm ET

-

MAY

7

11am ET -

Collections 101

Speaker: JoAnn Malz, CCE, ICCE, Director of Credit, Collections, and

Billing with The Imagine Group

Duration: 60 minutes

-

Author Chat: How to Lead When You’re Not in Charge

Author: Clay Scroggins

Duration: 90 minutes | Complimentary -

MAY

8

11am ET

In a Global Economy Marked by Protectionism, What Is Instore

for the Agri-Food Sector?

A particularly strategic sector, agri-food is one of the sectors in the midst of the current trade war between the United States and China.

Recently, Chinese authorities have taken steps to ban all agri-food imports from the United States, in response to the tariff increases announced by the Trump administration.

Commercial tensions and soybean prices trend downwards

The movements around soybean are a perfect illustration of the situation. A commodity that is widely used for both human consumption and livestock feed (like maize or wheat), soybean’s prices have experienced high volatility and a downward trend.

Thanks to its statistical model that forecasts selected commodity prices, Coface estimates that soybean prices will fall by 9% in 2019 compared to the previous year, due to both trade tensions between China and the United States, and to the serious outbreak of African swine fever. The latter has led Chinese pork producers to slaughter a large part of their livestock to limit the spread, and therefore to buy less soybean to feed them. At the same time, this situation has directly impacted global pork production, half of which is produced in China. Chinese consumers will therefore have to turn to other animal proteins, such as poultry and beef, leading to increased demand from major global exporters like Argentina and Brazil.

Another consequence of the U.S.-China trade tensions for the global agri-food sector is the transformation of "export routes" for certain raw materials, including soybeans and pork. Although some of the world's major soybean producers and exporters, such as Brazil and Argentina, could benefit somewhat from the situation in the medium term, risks to the agri-food sector as a whole remain high.

Other risks that weigh on global agri-food sector outlook

In addition to the aforementioned global protectionist context, there are other potential risks for agri-food companies, such as the African swine fever epidemic, or the fall armyworm that threatens the global maize market. In terms of structural risk, the sector is vulnerable to weather conditions that can affect crops, such as severe droughts or the El Niño phenomenon.

Finally, even though agri-food is strongly affected by a global economic environment marked by protectionist tensions, it is also often a key sector in free trade agreements, as evidenced by the recent agreement between the European Union and MERCOSUR.

Governments often negotiate these agreements to facilitate trade in products that would notably benefit their domestic agri-food sector. However, local farmers do not necessarily support them, and they are received with growing skepticism by part of the public opinion, sometimes leading to delays in the ratification of these free trade agreements by public authorities.

Lower for Longer: Rising Vulnerabilities May Put Growth at Risk

Tobias Adrian and Fabio Natalucci

The pace of global economic activity remains weak, and financial markets expect rates to stay lower for longer than anticipated in early 2019. Financial conditions have eased even more, helping contain downside risks and support the global economy in the near term. But loose financial conditions come at a cost: They encourage investors to take more chances in a quest for higher returns, so risks to financial stability and growth remain high in the medium term.

The latest edition of our Global Financial Stability Report highlights elevated vulnerabilities in the corporate and nonbank financial sectors in several large economies. These and other weak spots could amplify the impact of a shock, such as an intensification of trade tensions or a no-deal Brexit, posing a threat to economic growth.

This situation poses a dilemma for policymakers. On the one hand, they may want to keep financial conditions easy to counter a deterioration in the economic outlook. On the other hand, they must guard against a further buildup of vulnerabilities. The GFSR points to some policy recommendations, including deploying and developing, as needed, new macroprudential tools for nonbank financial firms.

Twists and turns

Since the last edition of the GFSR in April, global financial markets have been buffeted by the twists and turns of trade tensions and significant policy uncertainty. A deterioration in business sentiment, weakening economic activity and intensifying downside risks to the outlook have prompted central banks across the globe, including the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve, to ease policy.

Investors have interpreted central bank actions and communications as a turning point in the monetary policy cycle. About 70% of economies, weighted by GDP, have adopted a more accommodative monetary stance. The shift has been accompanied by a sharp decline in longer-term yields; in some major economies, interest rates are deeply negative. Remarkably, the amount of government and corporate bonds with negative yields has increased to about $15 trillion.

The result is even easier financial conditions but also a continued buildup of financial vulnerabilities, particularly in the corporate sector and among nonbank financial institutions.

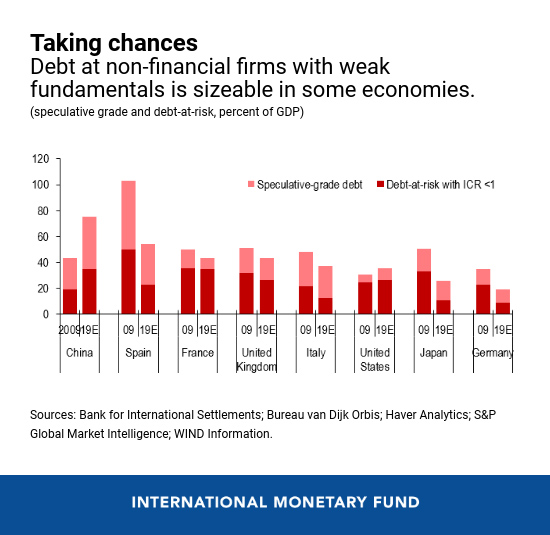

Corporations in eight major economies are taking on more debt, and their ability to service it is weakening. We look at the potential impact of a material economic slowdown—one that is half as severe as the global financial crisis of 2007-08. Our conclusion is sobering: Debt owed by firms unable to cover interest expenses with earnings, which we call corporate debt-at-risk, could rise to $19 trillion. That is almost 40% of total corporate debt in the economies we studied, which include the United States, China and some European economies.

Among nonbank financial institutions, vulnerabilities have risen since April and are now elevated in 80% of economies, by GDP, with systemically important financial sectors—a level similar to the height of the global financial crisis.

Very low rates have prompted institutional investors like insurance companies, pension funds and asset managers to reach for yield and take on riskier and less liquid securities to generate targeted returns. For example, pension funds have increased their exposure to alternative asset classes like private equity and real estate.

What are the possible consequences? Similarities in portfolios of investment funds could amplify a market sell-off, and illiquid investments by pension funds could constrain their traditional stabilizing role in markets. In addition, cross-border investments by life insurers could provoke spillovers across markets.

External debt is rising among emerging and frontier economies as they attract capital flows from advanced economies, where interest rates are lower. Median external debt has risen to 160% of exports from 100% in 2008 among emerging market economies. A sharp tightening in financial conditions and higher borrowing costs would make it harder for them to service their debts.

Unbalanced

Stretched asset valuations in some markets are also contributing to financial stability risks. Equity markets appear to be overvalued in the United States and Japan. In major bond markets, credit spreads—the compensation investors demand to bear credit risk—also seem to be too compressed relative to fundamentals.

A sharp, sudden tightening in financial conditions could unmask these vulnerabilities and put pressure on asset price valuations. So, what should policymakers do to tackle these risks? What tools can be deployed or developed to address the specific vulnerabilities identified in this report?

- Corporate debt-at-risk: stricter supervisory and macroprudential oversight, including targeted stress testing of banks and prudential tools for highly levered firms.

- Institutional investors: strengthened oversight and enhanced disclosures, including stepped-up efforts to mitigate leverage and other balance-sheet mismatches.

- Emerging and frontier markets: prudent sovereign-debt management practices and frameworks.

With financial conditions still easy so late in the cycle, and with vulnerabilities building, policymakers should act quickly to avoid putting growth at risk in the medium term. Uncertainty may reign today—but sound policy decisions, adopted soon, could help avoid the most dangerous outcomes.

Reprinted with permission from the IMF.

Week in Review Editorial Team:

Diana Mota, Associate Editor and David Anderson, Member Relations